Once considered to be incompetent in encoding proteins due to their simple monotonous DNA repetitions, tiny telomeres at the tips of human chromosomes now appear to have a powerful biological function that could help better understand cancer and aging.

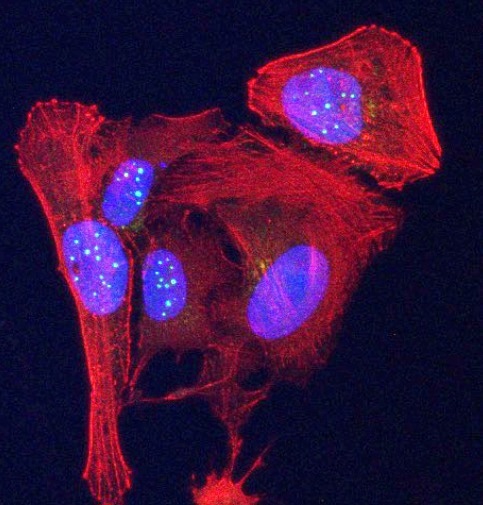

Newly discovered telomeric protein VR, (green spheres) is seen accumulating in nuclei (blue ovals) in human osteosarcoma cancer cells stained in red. Image Credit: Griffith Lab.

Newly discovered telomeric protein VR, (green spheres) is seen accumulating in nuclei (blue ovals) in human osteosarcoma cancer cells stained in red. Image Credit: Griffith Lab.

UNC School of Medicine scientists Taghreed Al-Turki, PhD, and Jack Griffith, PhD, reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science that telomeres possess genetic information to produce two small proteins, one of which they discovered is elevated in some human cancer cells as well as cells from patients suffering from telomere-related defects.

Based on our research, we think simple blood tests for these proteins could provide a valuable screen for certain cancers and other human diseases. These tests also could provide a measure of ‘telomere health,’ because we know telomeres shorten with age.”

Jack Griffith, Kenan Distinguished Professor, Microbiology and Immunology, UNC School of Medicine

Jack Griffith is also a member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Telomeres have a unique DNA sequence that consists of infinite repeats of TTAGGG bases that prevent chromosomes from sticking together. The Griffith laboratory demonstrated two decades ago that the end of a telomere’s DNA loops back on itself to form a tiny circle, concealing the end and preventing chromosome-to-chromosome fusions.

Telomeres shorten when cells divide, ultimately becoming so short that the cell can no longer divide properly, resulting in cell death.

Telomeres were discovered about 80 years ago, and because of their repetitive sequence, the established dogma in the field held that telomeres really cannot encode for any proteins, let alone ones with significant biological function.

In 2011, researchers in Florida working on an inherited form of ALS revealed that the culprit was an RNA molecule with a six-base repeat that could produce a series of toxic proteins consisting of two amino acids repeating one after the other via a novel mechanism.

In their study, Al-Turki and Griffith noticed a striking similarity between this RNA and the RNA produced by human telomeres, and they speculated that the same novel mechanism is at work.

They carried out experiments to demonstrate how telomeric DNA can direct the cell to produce signaling proteins known as VR (valine-arginine) and GL (glycine-leucine). Signaling proteins are mainly chemicals that cause a chain reaction of other proteins inside cells to perform a biological function that is essential for health or disease.

Al-Turki and Griffith then chemically synthesized VR and GL to investigate their properties using strong electron and confocal microscopes as well as cutting-edge biological methods, disclosing that the VR protein is present in higher levels in some human cancer cells as well as cells from patients suffering from diseases caused by telomere defects.

Al-Turki, a postdoctoral researcher in the Griffith lab, notes, “We think it’s possible that as we age, the amount of VR and GL in our blood will steadily rise, potentially providing a new biomarker for biological age as contrasted to chronological age. We think inflammation may also trigger the production of these proteins.”

When you go against current thinking, you are usually wrong because you are bucking many people who’ve worked so diligently in their fields. But occasionally scientists have failed to put observations from two very distant fields together and that’s what we did. Discovering that telomeres encode two novel signaling proteins will change our understanding of cancer, aging, and how cells communicate with other cells.”

Jack Griffith, Kenan Distinguished Professor, Microbiology and Immunology, UNC School of Medicine

Jack Griffith concludes, “Many questions remain to be answered, but our biggest priority now is developing a simple blood test for these proteins. This could inform us of our biological age and also provide warnings of issues, such as cancer or inflammation.”