The majority of chromosomes have existed for millions of years. The dynamics of a new, very young chromosome in fruit flies that is identical to chromosomes that develop in people and is connected with treatment-resistant cancer and infertility have now been discovered by Stowers Institute for Medical Research researchers. The findings could lead to the development of more tailored therapies for treating these conditions in the future.

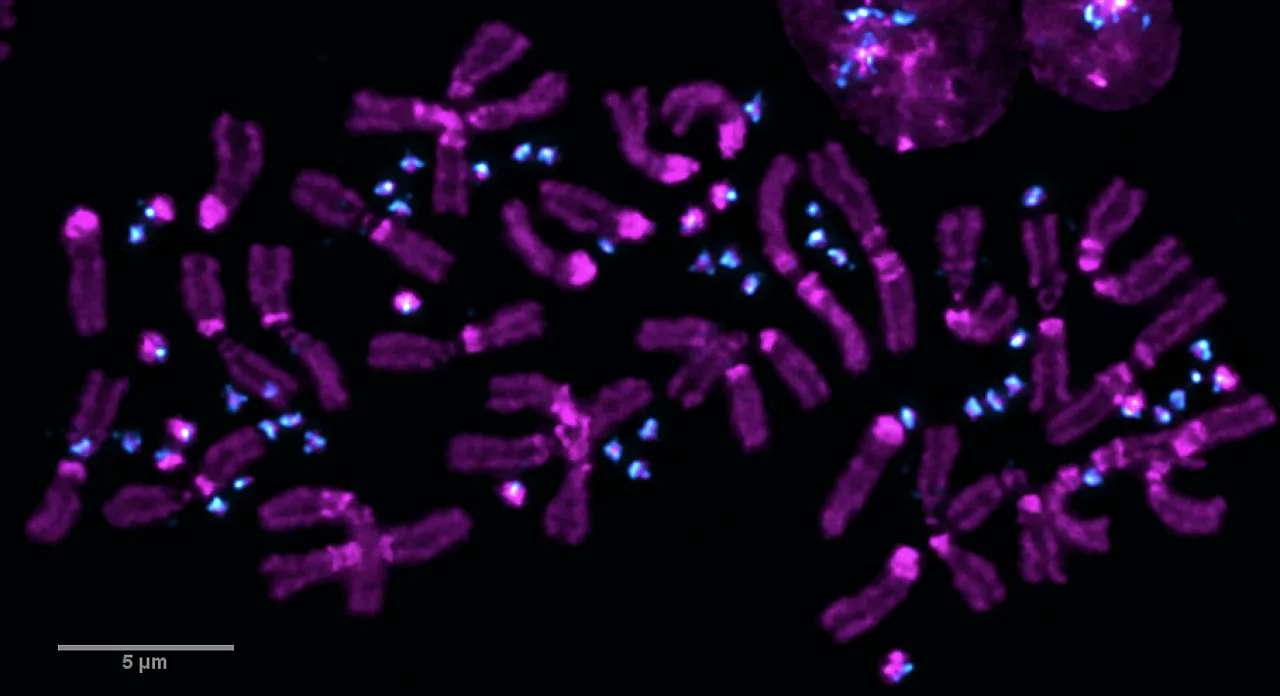

Paired chromosomes during meiosis. Essential A chromosomes are in magenta and B chromosomes are cyan. Image Credit: Stowers Institute for Medical Research.

Recent research published in Current Biology on May 4th, 2023, demonstrates how a tiny chromosome that appeared less than 20 years ago has lasted in a single lab-reared strain of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, and is linked to supernumerary (extra) chromosomes in humans.

I feel kind of like an astronomer who’s watching the birth of a star. We are getting to watch the birth of a chromosome and are starting to understand both its capabilities and limitations.”

Scott Hawley Ph.D., Investigator, Stowers Institute for Medical Research

The Hawley Lab was the first to identify these small, extra chromosomes, but little was known about their form, function, or behavior during cell division. Stacey Hanlon, Ph.D., a former Hawley Lab postdoctoral researcher, recognized that this discovery could provide an ideal system for investigating how new chromosomes emerge, which could lead to more effective cancer treatments and strategies to cure infertility.

Supernumerary chromosomes are prevalent in cancer cells and frequently interact with tumor-targeting drugs, making some malignancies, like osteosarcoma, difficult to treat. Furthermore, the presence of extra chromosomes in men might impair normal chromosome segregation during sperm production, resulting in infertility.

Being able to understand how supernumerary chromosomes arise and what their structures are can potentially illuminate their vulnerabilities. This may enable the development of potential therapeutic targets.”

Scott Hawley Ph.D., Investigator, Stowers Institute for Medical Research

These genetic components, known as B chromosomes (as opposed to the usual “A” set of necessary chromosomes), organically arose in a single experimental population of fruit flies in Hawley’s lab. In less than two decades, the researchers have witnessed chromosomal birth and evolution.

How does something like this new chromosome seem to emerge out of nowhere? More importantly, given that these newly born B chromosomes lack any known necessary genes for fruit fly function, how do they survive in a genome? In a nutshell, via deception.

“I like to call these B chromosomes genetic renegades. They do not follow the rules,” noted Hanlon.

Hanlon revealed that the fruit fly B chromosomes are sustained by a mechanism known as “meiotic drive,” which allows them to defy the normal principles of inheritance. During egg development, the B chromosomes drive their way into the next generation to assure their own persistence in more than half of the following generation.

“Their genetic background—meaning the unique features in the B chromosome flies’ genetic make-up—supports their preferential transmission to the next generation. That buys these guys evolutionary time to become a new chromosome, whether that’s picking up an essential gene or acquiring something that enables them to better cheat,” added Hanlon.

The meiotic drive is a potent force that can influence how genomes evolve. These findings, which originated in the Hawley Lab and are now being actively researched by Hanlon at her own lab at the University of Connecticut, can be utilized to better understand the mechanisms that maintain meiosis fair and ensure that cheaters, such as the B chromosomes, do not thrive.

Hanlon is also investigating how certain mutations might cause chromosome breakage and the development of new chromosomes, revealing the mechanism by which supernumeraries arise and become required components of a genome.

We’re always looking for Achilles heels to get rid of these kinds of things. If we can identify what encouraged their formation, we may be able to identify individuals more likely to form them and take better measures to look for and deal with them.”

Scott Hawley Ph.D., Investigator, Stowers Institute for Medical Research

Birth of a Chromosome

Researchers discuss their new findings and the impact of the work. Video Credit: Stowers Institute for Medical Research

Source:

Journal reference:

Hanlon, S. L., & Hawley, R. S. (2023). B chromosomes reveal a female meiotic drive suppression system in Drosophila melanogaster. Current Biology. doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.04.028.