Reviewed by Danielle Ellis, B.Sc.May 31 2023

The Francis Crick Institute has discovered three 4,000-year-old British cases of Yersinia pestis, the bacteria that causes the plague—the oldest evidence of the plague in Britain to date. The study was published in Nature Communications.

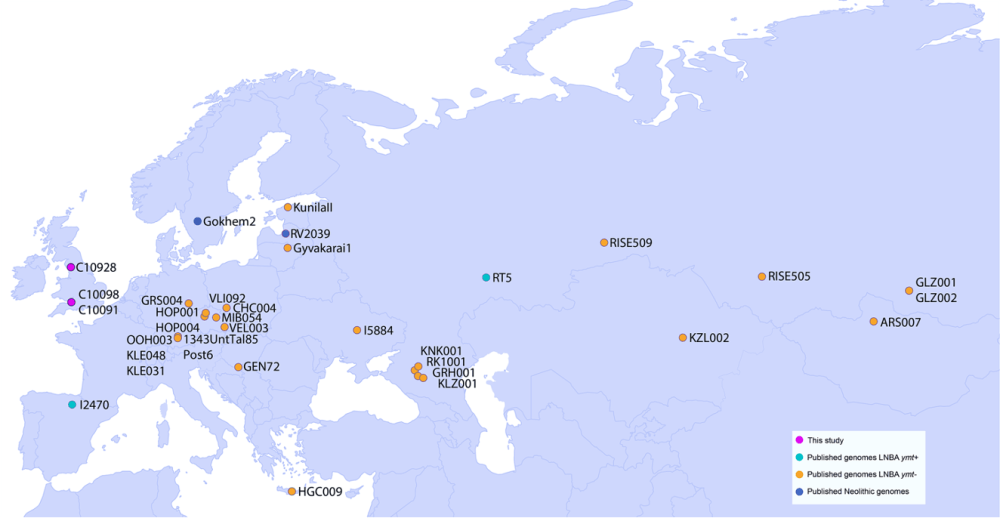

Map showing the distribution of LNBA Yersinia pestis strains. New genomes sequenced in this study are in purple. Image Credit: Pooja Swali (2023), Nature Communications.

Map showing the distribution of LNBA Yersinia pestis strains. New genomes sequenced in this study are in purple. Image Credit: Pooja Swali (2023), Nature Communications.

The researchers identified two cases of Yersinia pestis in human remains unearthed in a mass burial in Charterhouse Warren, Somerset, and one in a ring cairn monument in Levens, Cumbria, in collaboration with the University of Oxford, the Levens Local History Group, and the Wells and Mendip Museum.

They took tiny skeletal samples from 34 people across two sites to test for the presence of Yersinia pestis in teeth. This process is carried out in a specialized clean room facility, where they drill into the tooth and retrieve dental pulp, which can capture infectious disease DNA remains.

Researchers then analyzed the DNA and discovered three cases of Yersinia pestis in two children aged 10 to 12 years old when they died, and one woman aged 35 to 45. Radiocarbon dating was utilized to determine that the three people most likely lived in the same period.

The plague had earlier been detected in many individuals from Eurasia between 5,000 and 2,500 years before present (BP), a time frame encompassing the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age (termed LNBA), but had never been encountered in Britain before. The LNBA lineage’s vast geographic dissemination shows that this strain of the plague was easily transmitted.

The LNBA lineage was likely transported into Central and Western Europe by humans moving into Eurasia some 4,800 years ago, and this research implies that it expanded to Britain.

The researchers used genome sequencing to reveal that this strain of Yersinia pestis is extremely similar to the strain discovered in Eurasia at the same time.

The genomes found all lacked the yapC and ymt genes found in later strains of plague, the latter of which is known to play a crucial role in flea-borne plague transmission. This research previously showed that, unlike later plague strains like the one that caused the Black Death, this strain of the plague was not transmitted by fleas.

Since pathogenic DNA—DNA from bacteria, protozoa, or viruses that cause disease—degrades quickly in incomplete or eroded samples, it is indeed likely that more people at these burial sites were infected with the same strain of plague.

The Charterhouse Warren site is unusual because it differs from other funeral sites from the historical period; the people buried there appear to have died as a result of trauma. The experts believe that the mass burial was not caused by a plague outbreak, but that individuals may have been infected at the time they died.

The ability to detect ancient pathogens from degraded samples, from thousands of years ago, is incredible. These genomes can inform us of the spread and evolutionary changes of pathogens in the past, and hopefully help us understand which genes may be important in the spread of infectious diseases. We see that this Yersinia pestis lineage, including genomes from this study, loses genes over time, a pattern that has emerged with later epidemics caused by the same pathogen.”

Pooja Swali, Study First Author and PhD Student, The Francis Crick Institute

Pontus Skoglund, group leader of the Ancient Genomics Laboratory at the Crick, comments, “This research is a new piece of the puzzle in our understanding of the ancient genomic record of pathogens and humans, and how we co-evolved.”

We understand the huge impact of many historical plague outbreaks, such as the Black Death, on human societies and health, but ancient DNA can document infectious disease much further into the past. Future research will do more to understand how our genomes responded to such diseases in the past, and the evolutionary arms race with the pathogens themselves, which can help us to understand the impact of diseases in the present or in the future.”

Pontus Skoglund, Group Leader, Ancient Genomics Laboratory, The Francis Crick Institute

4,000-year-old plague DNA found in Britain

4,000-year-old plague DNA found in Britain. Video Credit: The Francis Crick Institute.

Source:

Journal reference:

Swali, P., et al. (2023). Yersinia pestis genomes reveal plague in Britain 4000 years ago. Nature Communications. doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38393-w.