Elizabeth King, Associate Professor in the Division of Biological Sciences at the University of Missouri, was inspired to spend her formative years studying science by a lifelong curiosity about the natural world and the diversity of life—and along the way, she discovered her passion for biology.

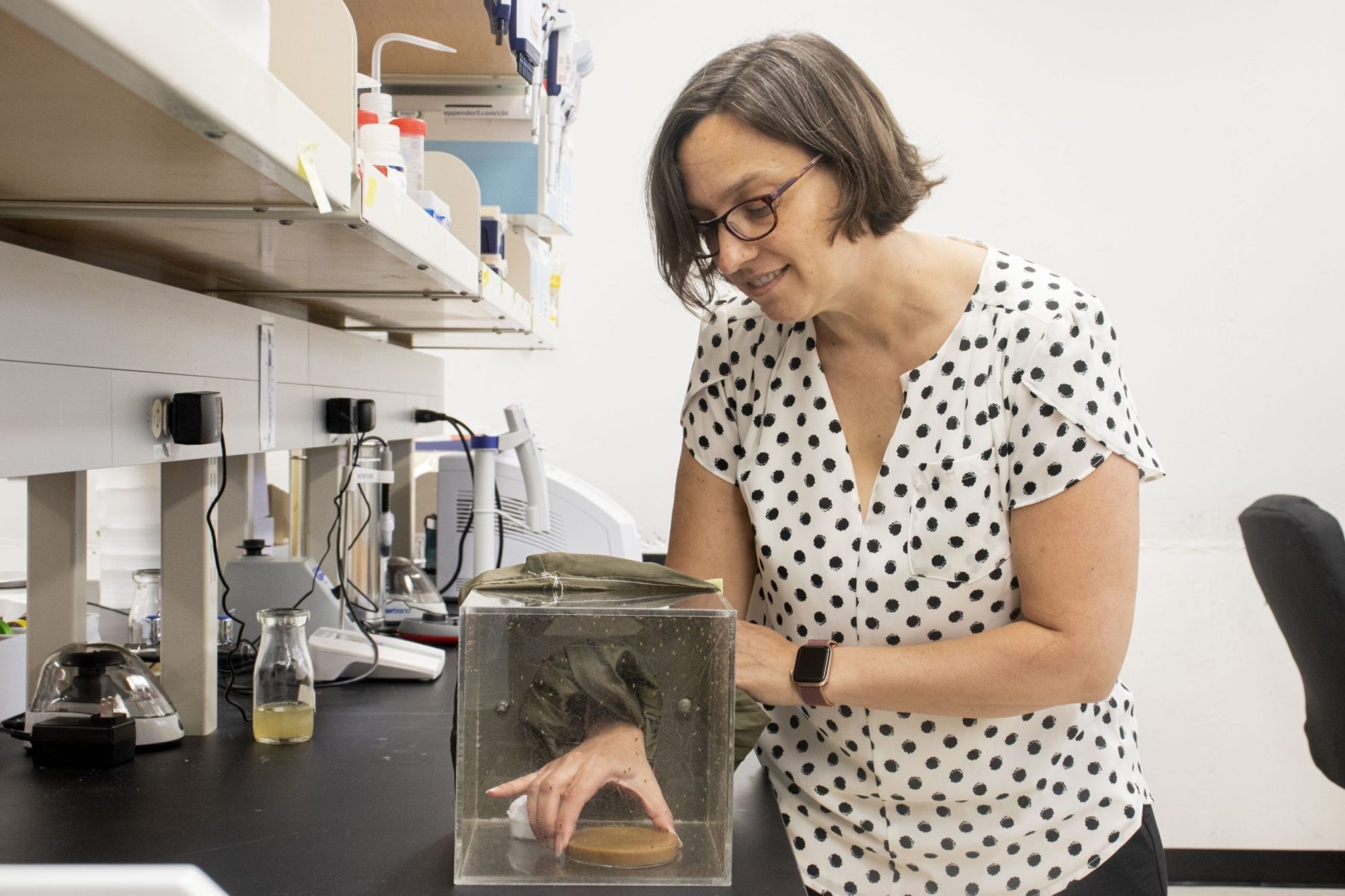

Elizabeth King, Associate Professor in the Division of Biological Sciences, checks the food source for a group of fruit flies in her lab at the University of Missouri. Image Credit: Pate McCuien/University of Missouri

Elizabeth King, Associate Professor in the Division of Biological Sciences, checks the food source for a group of fruit flies in her lab at the University of Missouri. Image Credit: Pate McCuien/University of Missouri

That foundation has encouraged her to pursue an ongoing career striving to improve the scientific understanding of genetic traits.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) gave King a five-year, $1.9 million grant to enhance her lab’s experimental biology study using a fruit fly model. The project’s purpose is to build a knowledge base around complicated qualities or features, such as the flying ability and endurance of a fruit fly, that are affected by the interconnection of many variables, including numerous genes and the environment.

According to King, the research will contribute to closing a scientific knowledge gap in this field of study.

Science has not fully grappled with the ‘complex’ part of complex traits, and that is left a significant knowledge gap in our understanding of the genetic basis of these traits. Our work embraces this complexity by focusing explicitly on the interconnectedness between multiple high-order traits and the sub-phenotypes that come together to shape them. Overall, this research will provide generalizable lessons about how genomes are connected to physiology to produce the interconnected set of traits that affect health across the lifespan.”

Elizabeth King, Associate Professor, Division of Biological Sciences, University of Missouri

While King’s research focuses on fundamental science knowledge, she expects that the data obtained over the course of the five-year experiment will be useful to other scientists investigating human genetics in the future.

For example, one element of the research will concentrate on trait hierarchies, or how traits are classified into phenotypes and sub-phenotypes. She claims that many human characteristics are structured similarly.

For instance, a person’s risk of a heart attack results from a combination of a lot of different phenotypes and sub-phenotypes found at different levels. So, with this project, we’re looking at traits structured in similar ways in flies, such as flight performance, and dissect the genetics across the genotype-to-phenotype map to see if we can come up with some general lessons about what these traits are really like because they’re so complex we haven’t really figured them out yet.”

Elizabeth King, Associate Professor, Division of Biological Sciences, University of Missouri

She further stated, “We have developed hypotheses for why that might be the case, and we are hoping to harness the power of the fly model to figure that out.”

Using fruit flies as a model to study universal principles throughout the diversity of life can also be extremely useful in understanding how traits operate in humans.

“Like we do with other species, fruit flies share common ancestry with humans. In a lot of cases once we figure out a gene’s function, we can then connect that trait to something similar in humans. It is estimated that around 75% of genes in the Drosophila genome have a relationship to disease-related genes found in humans,” King concluded.