National Institutes of Health researchers and their collaborators revealed fresh insights into healing and aging by studying how a small marine creature regenerates a completely new body from only its mouth. Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus, a small, tube-shaped critter that lives on the shells of hermit crabs, was sequenced by the researchers.

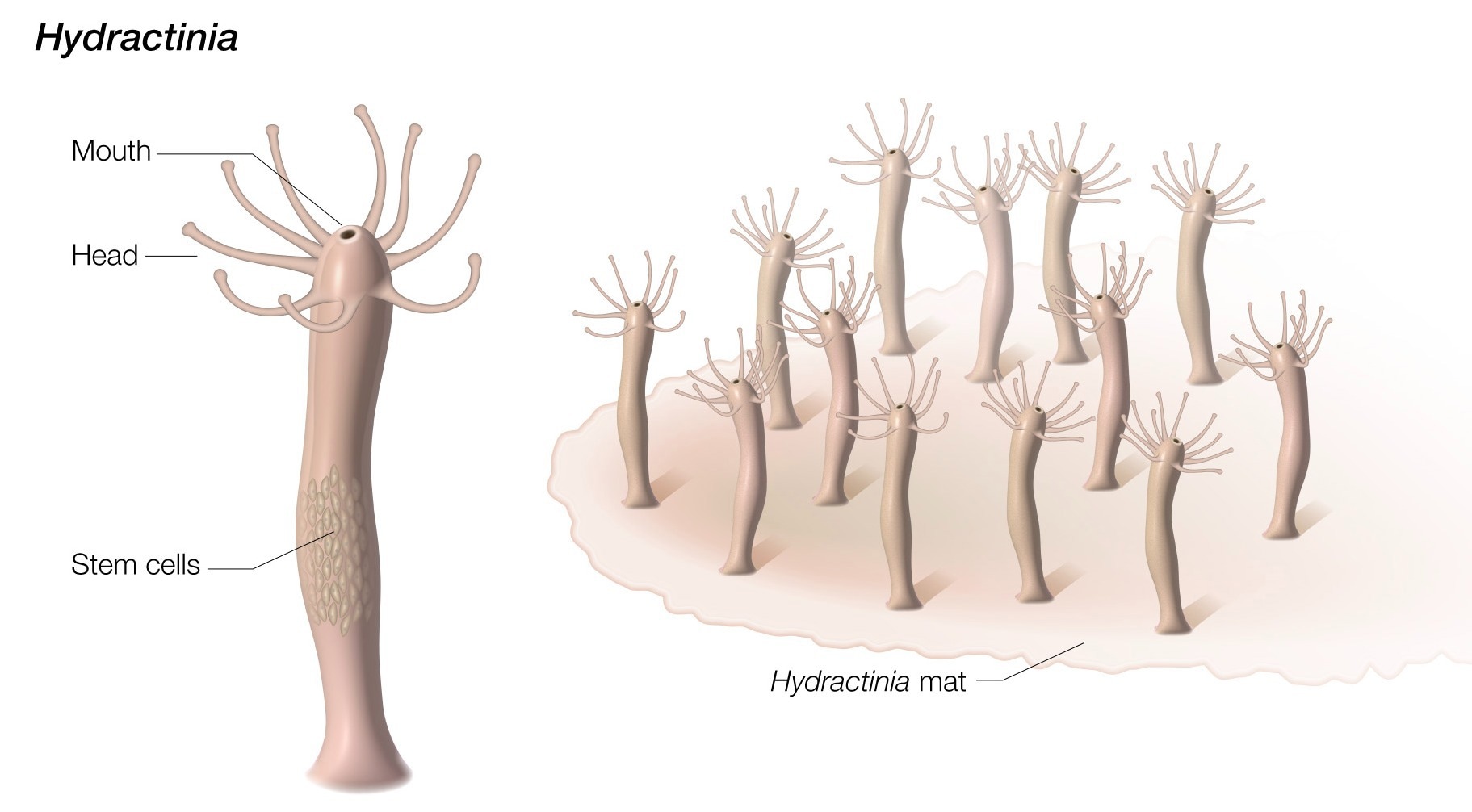

Hydractinia’s regeneration driving stem cells are stored in the lower trunk of the animal's body, far from the its mouth. Image Credit: Darryl Leja, NHGRI

Hydractinia’s regeneration driving stem cells are stored in the lower trunk of the animal's body, far from the its mouth. Image Credit: Darryl Leja, NHGRI

The scientists discovered a molecular signature linked to senescence, the biological aging process, just as the Hydractinia were starting to regenerate new bodies. The study published in Cell Reports stated that Hydractinia shows that the basic biological processes of healing and aging are connected, giving new insight into how aging evolved.

Studies like this that explore the biology of unusual organisms reveal both how universal many biological processes are and how much we have yet to understand about their functions, relationships, and evolution. Such findings have great potential for providing novel insights into human biology.”

Charles Rotimi, Ph.D., Director, Intramural Research Program, National Human Genome Research Institute

Understanding human health and disease depends on unraveling the evolutionary roots of basic biological processes like aging and healing. Humans are capable of regenerating in some ways, such as healing a fractured bone or even growing a damaged liver.

Other animals can regenerate various organs and replace whole limbs, including salamanders and zebrafish. However, creatures with simple bodies, like Hydractinia, frequently possess the most extreme regenerative capacities, including the capacity to develop an entirely new body from a single tissue fragment.

Senescence’s regenerative function is at odds with what has been discovered in human cells.

Most studies on senescence are related to chronic inflammation, cancer, and age-related diseases. Typically, in humans, senescent cells stay senescent, and these cells cause chronic inflammation and induce aging in adjacent cells. From animals like Hydractinia, we can learn about how senescence can be beneficial and expand our understanding of aging and healing.”

Andy Baxevanis, Ph.D., Study Senior Author and Senior Scientist, National Human Genome Research Institute

Previously, scientists discovered that Hydractinia possesses a unique population of stem cells for regeneration. Stem cells are helpful for developing new body components because they can differentiate into other types of cells.

Stem cells play a major role in development in humans, but highly regenerative species like Hydractinia employ stem cells continuously. In the bottom trunk of its body, the hydractinia stores its stem cells that promote regeneration.

However, when the mouth is removed by the researchers—a location remote from the stem cells—the mouth develops a new body. Although this process is not fully understood, adult cells of some highly regenerative species have the ability to transform back into stem cells when the organism is injured, unlike human cells, which are unable to change their fates.

The scientists, therefore, postulated that Hydractinia must produce fresh stem cells and look for molecules that could guide this process.

The researchers searched the genome of Hydractinia for sequences similar to those of senescence-related genes in humans when RNA sequencing indicated senescence. One of the three genes they discovered was “turned on” in cells close to the animal’s wound.

The ability of the animals to produce senescent cells was inhibited when the researchers removed this gene, and without the senescent cells, the animals were unable to produce new stem cells or regenerate.

To learn how Hydractinia avoids the negative consequences of senescence, researchers monitored the senescent cells of this organism. The animals unintentionally spat the senescent cells out of their mouths. While aging cells are hard to get rid of in humans, Hydractinia’s senescence-related genes could have played an important part in the evolution of aging.

The last time Hydractinia and its close relatives, jellyfish and corals, and humans shared an ancestor was almost 600 million years ago, and yet these creatures never age.

These qualities make Hydractinia a valuable resource for understanding the earliest animal relatives of modern animals. Therefore, the researchers propose that the primary purpose of senescence in the earliest creatures may have been regeneration.

Baxevanis added, “We still don’t understand how senescent cells trigger regeneration or how widespread this process is in the animal kingdom. Fortunately, by studying some of our most distant animal relatives, we can start to unravel some of the secrets of regeneration and aging—secrets that may ultimately advance the field of regenerative medicine and the study of age-related diseases as well.”

Source:

Journal reference:

Salinas-Saavedra, M., et al. (2023). Senescence-induced cellular reprogramming drives cnidarian whole-body regeneration. Cell Reports. doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112687