A retrotransposon, a parasitic DNA sequence that borrows the cell’s own machinery to accomplish its objectives, has been discovered.

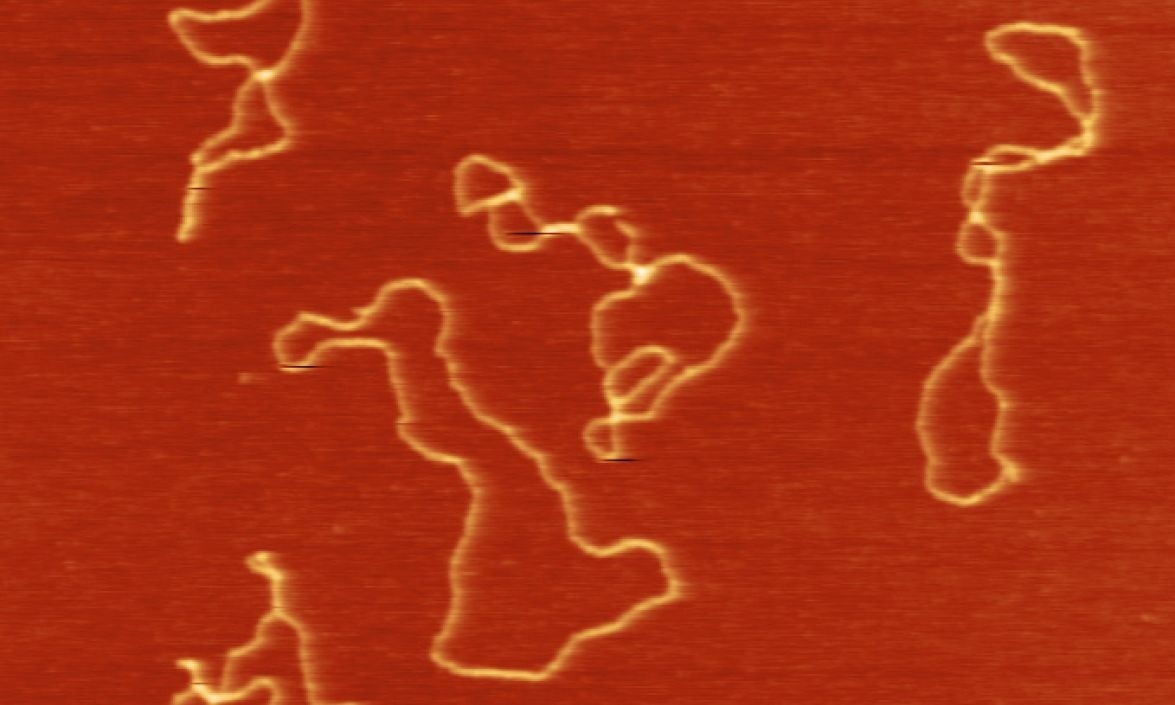

Ring-like circular DNA has been seen copying itself by borrowing some of the cell’s machinery, just as a virus does. Image Credit: Fu Yang, ZZ Lab, Duke University

Ring-like circular DNA has been seen copying itself by borrowing some of the cell’s machinery, just as a virus does. Image Credit: Fu Yang, ZZ Lab, Duke University

A Duke University group found that retrotransposons use a little-known piece of the cell’s DNA repair function to close themselves into a ring-like shape and generate a matching double strand. The study was published in the journal Nature.

The discovery challenges 40 years of conventional wisdom that these rings were merely a byproduct of poor gene copying. It could also shed light on cancer, viral infections, and immune responses.

Retrotransposons are 7,000-letter-long segments of DNA that copy and paste themselves into various parts of plant and animal genomes. They play a significant role in rewriting DNA and controlling how the cell uses its genes by doing so. Retrotransposons, inherited from both parents, are thought to be responsible for much of the variation and innovation in genes that drive evolution.

Numerous studies have indicated that these rings of DNA outside the chromosomes play a role in cancer development and progression, in part because they are known to contain cancer-causing oncogenes within their DNA sequences. HIV, the retrovirus that causes AIDS, is also known to generate circular DNA.

I think these elements are the source of genome dynamics, for animal evolution and even to affect our daily lives. But we are still in the process of appreciating their function.

Zhao Zhang, Assistant Professor, Pharmacology and Cancer Biology, Duke University

Zhao Zhang is also a Duke Science & Technology scholar.

Retrotransposons are quite usual, accounting for roughly 40% of the human genome and more than 75% of the maize genome, but how and where they copy themselves has always been a mystery.

Zhang displays a thick textbook on retroviruses that he used for this research. According to the books, the ring-like sequences are “created by recombining the two ends of linear DNA, and are just a dead end, a by-product of failed replication.”

Zhang’s team previously discovered that inherited retrotransposons use the “nurse cells” that assist the egg as factories to produce many copies of themselves, which are then distributed throughout the genome in the developing egg of the fly. This model system enabled the researchers to narrow their focus further to learn more about retrotransposons.

In their most recent study, they discovered that the majority of newly added retrotransposons were in this circular form instead of being incorporated into the host’s genome. The researchers then conducted a series of experiments in which they knocked out the cell’s DNA repair mechanisms one at a time to determine how and where the circles formed.

Alternative end-joining DNA repair, or alt-EJ for short, is a little-studied DNA repair mechanism that repairs double-stranded breaks. The retrotransposon sequences were using this part of the host’s repair machinery to sew the ends of their single-stranded DNA together and then create a matching double-strand with its DNA synthase. For good measure, the researchers confirmed that this process occurs within human cells as well.

So, retrotransposons are not really a random occurrence; they actually hijack a small portion of the cell’s machinery to produce more of themselves, just like viruses do.

Our discovery actually overturns the textbook model. We showed that the recombination event proposed by the textbook is not important to forming rings. Instead, it’s the alt-EJ pathway driving circle production. My lab currently is trying to test whether circular DNA can be an intermediate to make new genome insertions. We’re also testing whether circular DNA can be sensed by our immune system to trigger an immune response.

Zhao Zhang, Assistant Professor, Pharmacology and Cancer Biology, Duke University

Zhang concludes, “In the retroviral field and retrotransposon field, people think circular DNA is just a minor event, but our study is bringing circular DNA into the center stage. People should pay more attention to circular DNA.”

Source:

Journal reference:

Yang, F., et al. (2023). Retrotransposons hijack alt-EJ for DNA replication and eccDNA biogenesis. Nature. doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06327-7.