Researchers from the Universities of Leicester and Nottingham have been awarded nearly £600,000 to investigate how sexual development and gene shuffling inside the malaria parasite can help regulate malaria transmission.

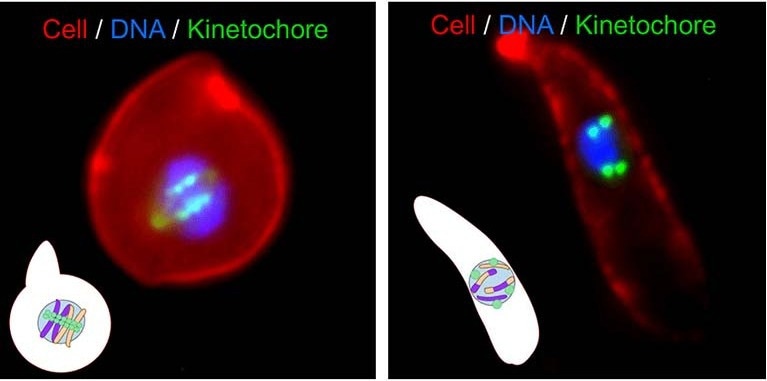

Gene shuffling during transmission stages of the malaria parasite. Image Credit: University of Leicester

Gene shuffling during transmission stages of the malaria parasite. Image Credit: University of Leicester

The investigation, headed by Dr. David Guttery of the University of Leicester and Professor Rita Tewari of the University of Nottingham, will concentrate on the molecular players associated with the development and transmission of the malaria parasite—one of the world’s deadliest killers.

This particular kind of cell division takes place during the meiotic process in the sexual cells of malaria parasites. All sexual organisms must undergo the fundamental process of meiosis to produce sex cells, or sperm and egg cells, which are then fertilized and undergo genetic reshuffling to produce offspring.

Numerous model organisms, such as yeast, Drosophila, and humans, have been used to thoroughly study the molecules controlling the process. Meiosis, which starts after fertilization in the ookinete, a stage of the malaria life cycle that resembles a banana and is essential for transmission from the mosquito, is very different in the malaria parasite.

We know that the malaria parasite shuffles genes during sexual reproduction (termed gene recombination), but what we don’t know is how it works. The funding we have received will open the door for us to discover this, and to potentially uncover new targets for therapies to control the spread of this devastating disease.”

Dr. David Guttery, University of Leicester

“To understand the basic machinery of cell division in malaria parasites, especially during the sexual stages of transmission, is crucial to stop the parasite in its tracks. Controlling the transmission of this devastating disease is as important as the disease itself. We have seen this in the case of COVID,” noted Professor Rita Tewari.

The Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) funded the research. The study includes associates from the Universities of Leicester (Dr. James Higgins), Nottingham (Dr. Stephen Gray and Professor Levi Yant), the Francis Crick Institute (Dr.Tony Holder), Oxford (Professors David Ferguson and Sue Vaughan), and Warwick (Dr Andrew Bottrill).

Professor Tewari’s research on cell division in male sex cells, funded by the European Research Council, will be supplemented by this study. Researchers from the Universities of Nottingham, Leicester, the Francis Crick Institute, and Groningen have published their findings in Trends in Parasitology.

The researchers highlight the process of meiosis and how it is so different in malaria parasites and discuss state-of-the-art technologies that could be used to solve the mystery of how meiosis and gene shuffling in the malaria parasite works, which could significantly and positively impact both human and animal health in the future.

Source:

Journal reference:

Guttery, D. S., et al. (2023) Meiosis in Plasmodium: how does it work? Trends in Parasitology. doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2023.07.002.