Alzheimer's disease impacts more than 6 million Americans, and it claims the lives of more than breast cancer and prostate cancer combined. However, a simple, single, accurate and definitive test of Alzheimer's remains elusive. As with most diseases, early diagnosis is important for outcomes; establishing a diagnostic tool for Alzheimer's is urgently needed to improve the quality and longevity of life of those suffering from the disease.

Image Credit: LightField Studios/Shutterstock.com

Recently, scientists from the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (EMPA) published a pilot study in the journal Science Advances, describing the development of a new blood test that relies on atomic force microscopy to produce diagnostic results for Alzheimer's disease. The platform could transform the nature of the disease by allowing doctors to initiate treatment at earlier stages before irreversible brain damage occurs. The establishment of such a diagnostic tool may also encourage more people to come forward for a test, resulting in more people accessing treatment, which may effectively slow the progression of their disease.

Atomic force microscopy opens the door to definitive a diagnostic method for Alzheimer's

Physicist Peter Nirmalraj of EMPA set out to gain a deeper understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease to guide the development of new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Along with colleagues, Nirmalraj conducted a study that aimed to both detect the beta-amyloid peptides and tau proteins associated with Alzheimer's disease as well as define their variable shape and concentrations in the blood.

Currently, methods exist that calculate the total amount of beta-amyloid peptides and tau proteins in body fluids. However, these techniques are limited in that they do not visualize the differences in the shape of the protein accumulations. The new study aimed to identify these shapes at the nanometer scale without destroying the sample.

Alongside neurologists at the Cantonal Hospital in St. Gallen, the EMPA team completed their preliminary study. Blood samples collected from 50 patients with Alzheimer's and 16 healthy participants were analyzed using atomic force microscopy (AFM). The surfaces of roughly 1,000 red blood cells per sample were investigated via AFM without knowledge as to whether the origin of the sample was a person with Alzheimer's or not.

Using the AFM-collected data, the EMPA researchers determined the size, structure, and texture of the accumulations of protein found on the red blood cells. This data was compared against clinical data provided by neurologists. The results revealed a discernible pattern that indicated a person's disease stage from their blood sample. Those with Alzheimer's disease had large quantities of protein fibers made up of beta-amyloid peptides and tau proteins. In healthy participants, these fibers were only found in small numbers.

The results show the potential of leveraging AFM technology into a reliable and accurate diagnostic platform. While more research and development are needed, the initial results indicate that it may be possible to establish a blood test to diagnose Alzheimer's disease. This would offer a faster and more straightforward route to a diagnosis, which is urgently needed.

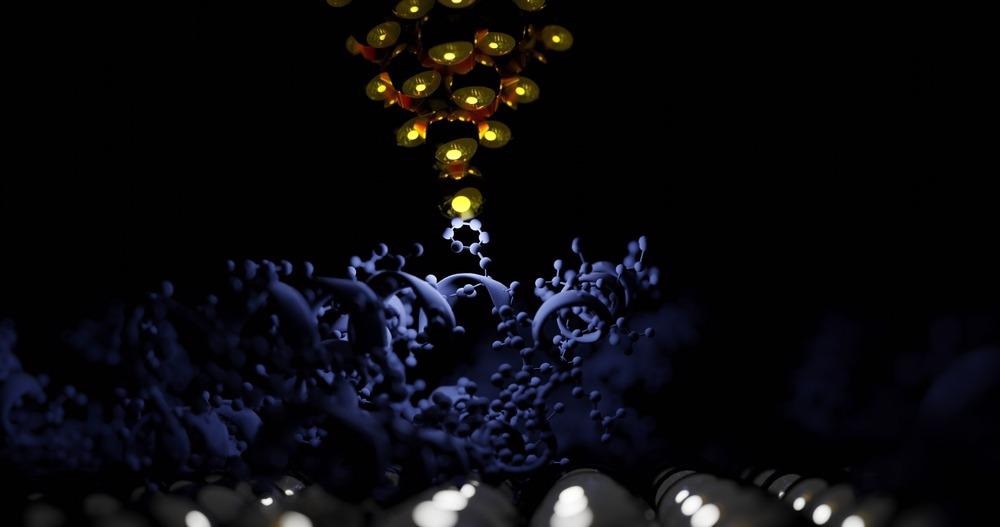

Image Credit: sanjaya viraj bandara/Shutterstock.com

The importance of early diagnosis in Alzheimer's

As with most diseases, the earlier Alzheimer's is detected, the better chance a person has of benefiting from the available treatment. It also gives those with Alzheimer's the chance to participate in clinical trials, which may give them access to a more effective therapeutic while contributing to the advancement of Alzheimer's research.

Currently, the route to Alzheimer's diagnosis is not simple. It often involves numerous psychological and physical tests and involves the collaboration of many medical professionals with different specialties. Often, lumbar punctures are required to access and analyze cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which can be unpleasant for the patient.

A simple blood test would drastically improve current diagnostic methods and encourage people to come forward at earlier stages. However, more research is likely needed before the AFM blood test is clinically available. The following steps would see the test developed further and trialed on a larger number of participants at different stages of the disease.

If successful, the AFM blood test may help millions access treatment at earlier stages of their disease. As a result, clinical outcomes for those with Alzheimer's may improve. Additionally, the test might make more participants with early-stage disease available for clinical trials, which may lead to the development of more effective treatments.

At this stage, these predictions are purely hypothetical. However, the initial findings are positive and give hope to those currently living with or who will potentially go on to develop Alzheimer's. Given that over the pandemic, deaths related to all dementias (of which Alzheimer's is a type) have risen by 16%, it is now a key time to establish diagnostic and therapeutic advances in this field.

Further Reading