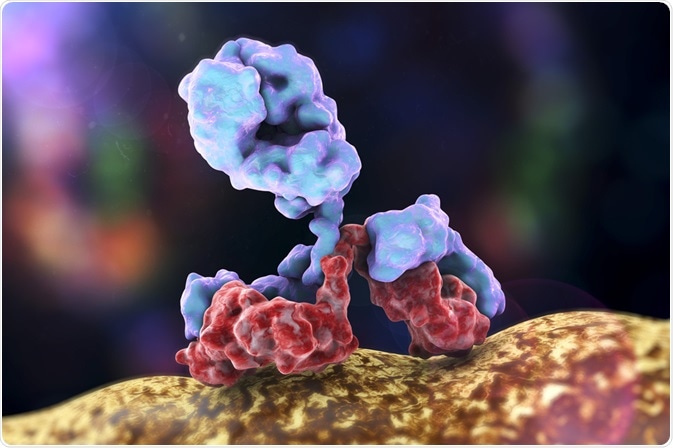

Over the last decade monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been one of the fastest-growing classes of pharmaceutical drugs. As more potential targets are identified through a greater understanding of molecular mechanisms underlying disease, it offers opportunities for the development of new mAb-based drugs.

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Key areas over the last decade have included cancer immunotherapy, inflammatory diseases, and certain autoimmune diseases. There have also been developments in the structure of mAbs, including antibody fragments, bispecific antibodies, and polyclonal antibodies.

Other areas include diagnostic and analytical uses for mAbs as an important tool in biochemistry. However, this article will focus on the new disease areas undergoing development for the clinical use of mAbs.

Autoimmune disease

Immunotherapy is a key area of treatment against autoimmune diseases. They can help to block autoantibodies from binding to their target, causing the immune system to act against the host’s cells.

Many treatments for Alzheimer’s disease target the amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide. Passive immunization with mAbs has been a key area of research within anti-Aβ therapy options, but trials have gained conflicting results.

For example, in phase II/III trial of Gantenerumab, including 799 participants, no significant improvements were measured in either brain activity or Aβ levels. However, patients with the fastest progression of the disease may have benefited.

A common explanation for these conflicting results has been the use of participants who are in the latter stages of the disease. The problem with addressing this is the difficulty of obtaining the same size of the study group, as it is harder to find people diagnosed in the early stages of disease progression.

Overall though, a more complete understanding of Alzheimer’s disease may be required before immunotherapy can see significant results.

The specific role of Aβ is still poorly understood, particularly whether its role is closer to being a symptom or cause of disease. Different targets for mAbs may be an area for research as the molecular mechanisms of Alzheimer’s are better understood.

.jpg)

Image Credit: Juan Gaertner/Shutterstock.com

Coronavirus

Recent advancements in the development of mAbs against coronavirus, specifically SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, could represent a potential avenue for prophylaxis or treatment of the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2.

Passive immunization of patients with mAbs would unlikely to result in an outright cure but may help to reduce the severity of disease and limit the virus from replicating.

This could be especially useful in patients suffering from moderate to severe disease and help to increase survival rates in these individuals.

Both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 enter the host cell via the receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2). This represents a potential target for immunotherapy, preventing the virus from binding with the host cell. A variety of mAbs have been proposed against ACE-2, but none have been approved.

An alternative target would be the spike protein on the virus that binds with the receptor. While the structure of SARS-CoV is known, further understanding of the structure and mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis would be required.

The pandemic nature of SARS-CoV-2 would likely mean that using a mAb as prophylaxis would not be feasible except in the most vulnerable patients, as it would not be possible to produce a high enough quantity for global use.

Whether mAb research could result in the development of a therapeutic for SARS-CoV-2 is up for debate. However, this area should be an area for research in the future regardless, as recent history shows us that there is a strong likelihood of future coronavirus outbreaks.

.jpg)

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Fungal infections

As the incidence of systemic fungal infections increases there is a greater need for vaccines or therapy. Changes in climate, worldwide travel, and more immunocompromised individuals have contributed to this increase.

Infection with Cryptococcus neoformans is often associated with HIV infection. As people are living longer with anti-retro virals, more people are susceptible to this species. A major component of C. neoformans pathogenesis is its ability to downregulate the immune response.

Capsular polysaccharides are important in doing this and are therefore a good target for mAbs. A study generated a mAb targeting a capsular polysaccharide, resulting in the clearance of the antigen from the serum of mice and increased overall survival of cryptococcosis.

Another mAb that acted against C. neoformans polysaccharide, 18B7, was shown to be both effective and safe. But it had funding issues and clinical trials had to be stopped prematurely.

Other mAbs have also shown promising results in clinical trials. Mycograb, which acts against a chaperone protein in Candida albicans, was shown to be clinically effective, but there were problems in production.

The use of mAbs in the treatment of systemic mycoses represents a promising area of research. However, issues in the cost-effectiveness and efficiency of production need to be improved to make it a viable option.

The problems with funding indicate a lack of economic or political will by pharmaceutical companies and governments to commit to fungal immunotherapy.

References

- Boniche, C. et al. (2020) ‘Immunotherapy against systemic fungal infections based on monoclonal antibodies’, Journal of Fungi. doi: 10.3390/jof6010031.

- van Dyck, C. H. (2018) ‘Anti-Amyloid-β Monoclonal Antibodies for Alzheimer’s Disease: Pitfalls and Promise’, Biological Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.08.010.

- Shanmugaraj, B. et al. (2020) ‘Perspectives on monoclonal antibody therapy as a potential therapeutic intervention for Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19)’, Asian Pacific journal of allergy and immunology. NLM (Medline), pp. 10–18. doi: 10.12932/AP-200220-0773.

Further Reading