Autoantigens are normal proteins or complexes of proteins recognized by the immune system of autoimmune patients. In normal circumstances, the human immune system can differentiate between hetero-antigens (foreign antigens) and autoantigens (or self-antigens). However, in some autoimmune diseases, the immune system cannot differentiate between them, leading to the generation of autoantibodies against autoantigens.

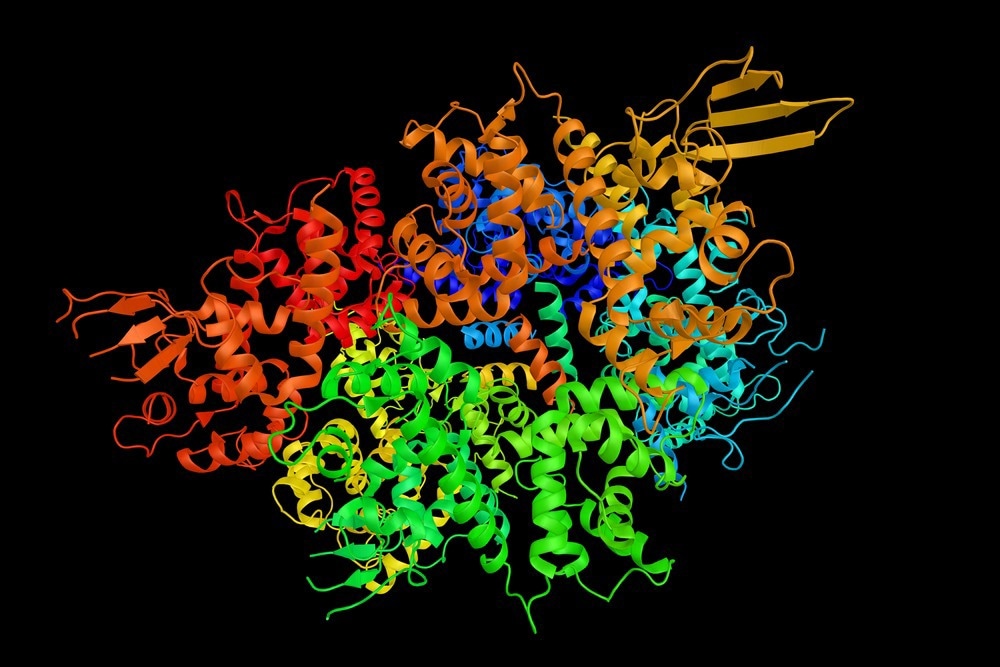

Image Credit: ibreakstock/Shutterstock.com

Overview of autoantigens

Autoimmunity is the result of specific immune responses directed against self-antigens or autoantigens. Tolerance is the ability of the immune system to avoid responsiveness to self-antigens or to prevent immune auto-aggression. Autoimmunity results from the failure of self-tolerance. It is widely accepted that autoimmune reactions are part of the physiological functioning of immunity. There are low concentrations of natural self-reactive antibodies, which are usually IgM isotypes having low avidity for the antigens, in the serum of healthy people. They may help the clearance of senescent cells and autoantigens, preventing the activation of cognate autoimmune reactions. However, these autoantibodies, usually IgG isotypes with high avidity for the antigens, are detected at relatively high concentrations in autoimmune patients.

Under normal circumstances, immunological tolerance regulates autoreactive T cells and autoantibodies, usually detected in healthy people. Anergy, clonal deletion, and clonal ignorance, which are examples of regulatory mechanisms, help regulate peripheral T cells. Specific triggers could pathologically activate these regulatory mechanisms, leading to the initiation of autoimmune responses. The immune system has different mechanisms to suppress the immune responses to the self-antigens, and the disturbance of these regulatory mechanisms leads to autoimmune diseases.

The formation of autoantigens is due to mutation, neoantigen production, or display of formerly hidden autoantigens. Genes producing self-proteins could mutate and create a novel immunogenic protein called neoantigen. Medications and viral infections could produce neoantigens, which can stimulate immune responses.

Autoantigens are normally protected from immunity via the absence of blood vessels, some anatomic barrier such as testes, or cellular structure (such as eyes) that push immunocompetent cells to go for programmed cell death. Infections of traumatic reactions could expose autoantigens, leading to stimulation immunity and damage to the tissues. Autoantigen may serve as a chemoattractant that recruits innate immune cells to tissue damage sites.

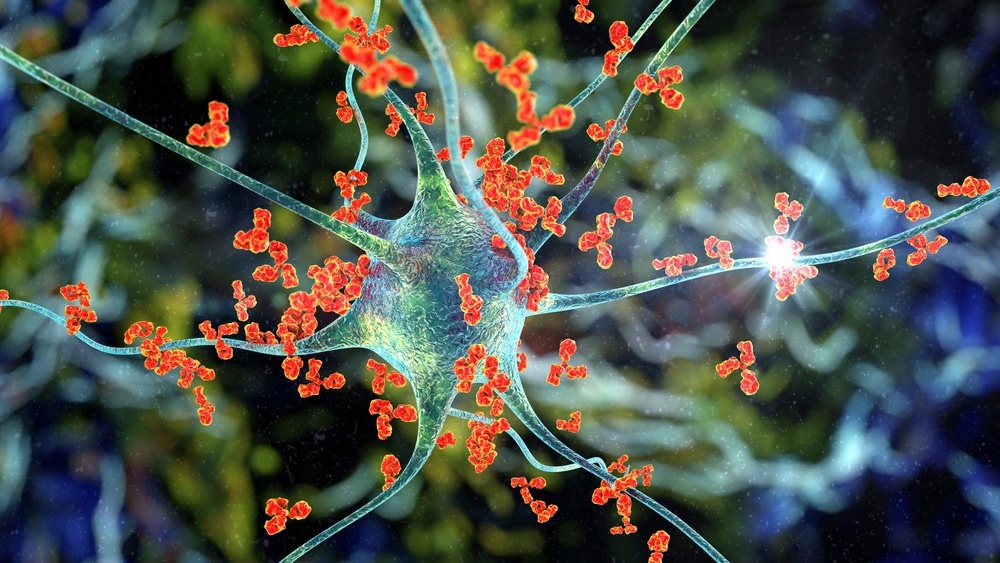

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Autoantigens in autoimmunity

Autoimmune diseases occur when specific adaptive immune responses are mounted against autoantigens or self-antigens. Antigen clearance is the consequence of adaptive immunity against foreign antigens or invaders. While cytotoxic T cells or CD8+ T-cells destroy virally infected cells, soluble antigens are cleared by the production of immune complexes of antigen and antibody, which are engulfed by mononuclear phagocytic cells like macrophages.

If adaptive immune responses develop against autoantigens, it is nearly impossible to eliminate the antigen completely, leading to sustained immune responses. Therefore, the effector immunity pathways lead to chronic inflammatory tissue injury. There is a close similarity between the mechanisms of tissue damage in autoimmune diseases and those observed in protective immunity and hypersensitivity diseases. T-cell responses to autoantigens can lead to direct or indirect damage to tissues.

CD8+ T-cell responses and pathogenic activation of macrophages by T helper cells can cause severe damage to the tissues. However, improper T-cell help to self-reactive B cells can trigger deleterious autoantibody response. A transient autoimmune response is common, but if it is sustained, this can lead to permanent tissue damage.

There are two categories of autoantigens: organ-specific and systemic autoantigens. Organ-specific autoantigens include Graves' disease, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and type I diabetes. Graves' disease, an autoimmune disease that can cause hyperthyroidism, is characterized by the antibody formation of the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptors in the thyroid glands.

Hashimoto's thyroiditis, an autoimmune disease that can cause hypothyroidism, is characterized by the formation of antibodies to thyroid peroxidase. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease characterized by forming antibodies against pancreatic β cells (insulin-producing cells).

On the other hand, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is marked by the detection of antibodies to antigens that are ubiquitous and abundant in all human cells, like anti-chromatin antibodies and antibodies to proteins of the pre-mRNA splicing machinery (the spliceosomes) within the cells.

Sources:

- Miller, Frederick W., et al. "The role of an autoantigen, histidyl-tRNA synthetase, in the induction and maintenance of autoimmunity." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 87.24 (1990): 9933-9937.

- Antiochos, Brendan, and Antony Rosen. "Mechanisms of Autoimmunity." Clinical Immunology. Elsevier, 2019. 677-684.

- Ilinskaya, Anna N., and Marina A. Dobrovolskaia. "Understanding the immunogenicity and antigenicity of nanomaterials: Past, present and future." Toxicology and applied pharmacology 299 (2016): 70-77.

- Yamamoto, Kazuhiko. "Mechanisms of autoimmunity." Autoimmune Diseases (2004): 403.

- Okazaki, Kazuichi, Kazushige Uchida, and Toshiro Fukui. "Recent advances in autoimmune pancreatitis: concept, diagnosis, and pathogenesis." Journal of gastroenterology 43.6 (2008): 409.

- Janeway Jr, Charles A., et al. "The complement system and innate immunity." Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 5th edition. Garland Science, 2001.

- Mak, Tak W., and Mary E. Saunders. "The Immune Response: Basic and Clinical Principles." (2007): 220-221.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jan 30, 2023