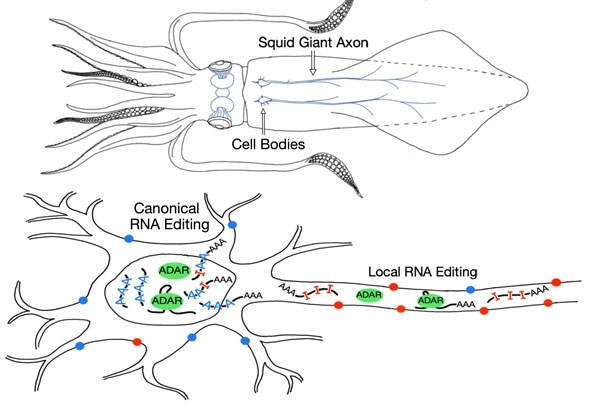

Researchers have recently discovered that squid can vastly edit their own genetic instructions, inside the nucleus of their neurons and also inside the axon.

This finding shows yet another super-power of the ingenious squid. Axons are long and thin neural projections that convey electrical impulses to other various neurons.

Top, schematic of squid anatomy showing the location of the “giant axon,” an unusually large neural projection that partly controls the squid’s jet propulsion system, used for very fast movement, attacks, and escapes. Below, schematic of a neuron, showing the location of the nucleus where all RNA editing was previously thought to occur, and the axon, where local RNA editing was identified in squid. Image Credit: Vallecillo-Viejo et al, Nucl. Acids Res., 2020.

For the first time, researchers were able to observe how genetic information is edited outside of the nucleus of an animal cell. The research, headed by Isabel C. Vallecillo-Viejo and Joshua Rosenthal at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), Woods Hole, was recently published in the Nucleic Acids Research journal.

This latest finding gives another twist to the central dogma of molecular biology, which states that genetic data is consistently passed from DNA to messenger RNA for protein synthesis.

Back in 2015, Rosenthal and collaborators found that squids are capable of “editing” the instructions of their messenger RNAs to an unusual extent—orders of magnitude more than human beings are capable of—enabling them to optimally adjust the kind of proteins that will be created in the nervous system.

But we thought all the RNA editing happened in the nucleus, and then the modified messenger RNAs are exported out to the cell. Now we are showing that squid can modify the RNAs out in the periphery of the cell. That means, theoretically, they can modify protein function to meet the localized demands of the cell. That gives them a lot of latitude to tailor the genetic information, as needed.”

Joshua Rosenthal, Study Senior Author and Senior Scientist, Marine Biological Laboratory

The researchers also demonstrated that the messenger RNAs are edited in the axon of the nerve cell at rates that are relatively higher than those in the nucleus.

Axon dysfunction in humans has been linked to several neurological diseases. The latest insights provided by the current research could potentially speed up the efforts of biotech firms that look to exploit this natural editing process of RNAs in human beings for therapeutic benefits.

Researchers from The University of Colorado at Denver and Tel Aviv University teamed up with MBL investigators for this study.

Earlier, Rosenthal and collaborators had demonstrated that marine creatures like cuttlefish and octopus largely depend on mRNA editing to diversify the proteins that can be created by them in the nervous system. Along with squid, these creatures are known for their remarkably advanced behaviors, in relation to other invertebrates.

Source:

Journal reference:

Vallecillo-Viejo, I. C. et al. (2020) Spatially regulated editing of genetic information within a neuron. Nucleic Acids Research. doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa172.