Similar to many other animals, fruit flies engage in many different courtships and fighting behaviors. Researchers from the Salk Institute have now exposed the molecular mechanisms through which a pair of sex-determining genes influences the behavior of fruit flies.

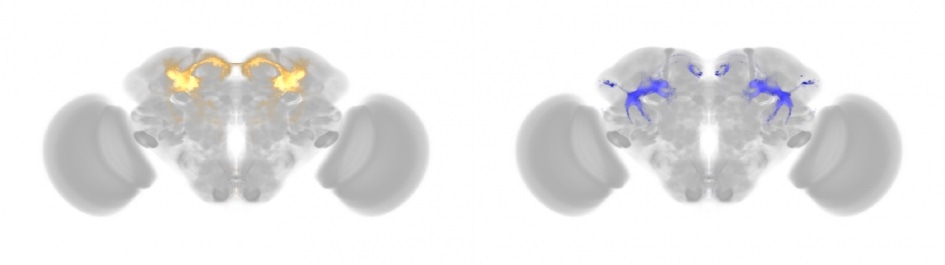

Researchers studied how sex-determining genes affect neurons known to control courtship (shown in orange on the left) and aggression (shown in blue on the right) in fly brains. Image Credit: Salk Institute.

The researchers demonstrated that the courtship and aggressive behaviors of the male flies are regulated by a couple of distinct genetic programs. The study’s findings, published in the eLife journal on April 21st, 2020, reveal the complexity of the relationship between behavior and sex.

Courtship and aggression seem to be controlled somewhat separately by these two genes. Having behaviors controlled by different genetic mechanisms can have some benefits in terms of evolution.”

Kenta Asahina, Study Senior Author and Assistant Professor, Molecular Neurobiology Laboratory, Salk Institute

This means, a fly population that is facing evolutionary pressure to contend more, maybe due to restricted resources, can develop aggressive behaviors without impacting courtship, Asahina explained.

Male fruit flies mainly display their aggressive behavior toward other males and show their courtship behaviors, which include a sequence of songs and movements, toward female flies.

Over time, these two behaviors are reinforced by evolution because the potential of the male flies to attract females and compete with other males directly impacts their capability to mate and thus pass on their genes.

The scientists already knew which types of neurons in the brain are significant for regulating courtship and aggressive behaviors. Generally, research had proposed that unique brain cells, known as P1/pC1 neurons, encourage both aggression and courtship, whereas Tk-GAL4FruM neurons particularly support aggression.

The researchers were also aware that the two sex-determining genes, doublesex (dsx) and fruitless (fru), played crucial roles in this behavior. Yet, the association between the behaviors and the genes continued to be vague.

In the latest study, Asahina and his collaborators raised Drosophila fruit flies that comprised light-activatable models of the aggression and courtship neurons. By shining a light on the fruit flies, the researchers could switch on the neurons at any time.

They then modified the dsx or fru genes in a few of these male fruit flies. Then, using machine-learning, they created an automated system to examine the videos of the fruit flies and count the number of times they performed the courtship or aggressive behaviors.

We made a computer system to capture aggressive behaviors and courtship behaviors to more quickly and accurately count actions. Getting the program to work was actually difficult and time-consuming but in the end, it made it easier for us to get good data.”

Kenichi Ishii, Study Co-Author and Postdoctoral Fellow, Salk Institute

Ishii is the co-first author of both the new papers.

The scientists discovered that the dsx gene was needed for the formation of courtship-inducing neurons, the courtship neurons were absent when the fruit flies had the female version of the dsx gene.

By contrast, the fru gene played an entirely different role, without this gene, the flies could still be persuaded to carry out their courtship behaviors by stimulating the courtship neurons, but the courtship was still directed at both females and males, implying that the fru gene was needed for flies to distinguish between the two sexes.

However, where aggression was concerned, the findings were actually the reverse: It was the fru gene and not the dsx gene that was needed to stimulate the aggression neurons to promote fighting in male fruit flies.

“This is an important example of the neurobiological differences between sexes and what kind of approaches we can use to study sexually-linked behaviors,” added Asahina, who also holds the Helen McLoraine Developmental Chair in Neurobiology.

I think the interesting part of this understands that sex is really not a binary thing, A lot of factors come together to control behaviors that differ between the sexes.”

Margot Wohl, Study Co-Author and Doctoral Student, UC San Diego

Considering that sex determination in flies is quite different than in humans, fruit flies lack sex hormones, for instance, the latest findings do not expand on how biological sex may affect behaviors in humans.

Nevertheless, according to Asahina, his method, the integration of sex-linked gene manipulation and optogenetics, may prove useful in interpreting behaviors that differ by sex in other kinds of animals.

Source:

Journal reference:

Ishii, K., et al. (2020) Sex-determining genes distinctly regulate courtship capability and target preference via sexually dimorphic neurons. eLife. doi.org/10.7554/eLife.52701.