Melanoma accounts for only about 1% of skin cancers but leads to most of the skin cancer-related deaths. Although there are treatments for this acute disease, the drugs can differ in their effectiveness based on the individual.

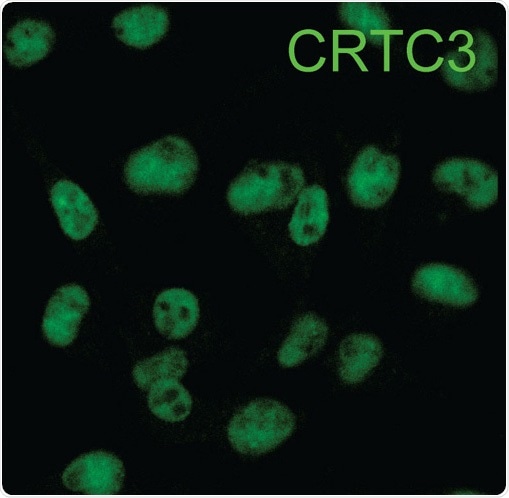

A microscopic view showing that the CRTC3 protein is located in the nucleus of melanoma cells. Image Credit: Salk Institute.

A new study led by the Salk Institute offers a new understanding about a protein known as CRTC3—a genetic switch that can possibly be targeted to come up with new treatments for melanoma by maintaining the switch turned off. The study was published in the Cell Reports journal on May 18th, 2021.

“We’ve been able to correlate the activity of this genetic switch to melanin production and cancer,” stated Marc Montminy, corresponding author of the Salk study and a professor in the Clayton Foundation Laboratories for Peptide Biology.

Melanoma occurs when pigment-producing cells, called melanocytes, which give skin its color, mutate and start to proliferate uncontrollably. These mutations can make proteins, such as CRTC3, to induce the cell to produce an abnormal amount of pigment or to migrate and turn more invasive.

Scientists are aware that the CRTC class of proteins (including CRTC1, CRTC2, and CRTC3) contribute to pigmentation and melanoma. However, it has been very difficult to obtain accurate details regarding the individual proteins.

This is a really interesting situation where different behaviors of these proteins, or genetic switches, can actually give us specificity when we start thinking about therapies down the road.”

Jelena Ostojić, Study First Author and Principal Scientist, DermTech

The researchers noticed that when CRTC3 in mice was eliminated, it led to a change in color in the coat color of the animal, showing that the protein is required for melanin synthesis. Their experiments also demonstrated that when the protein was lacking in melanoma cells, the cells migrated and invaded less, which implies that they were less aggressive. This indicates that suppression of the protein could be advantageous for disease treatment.

For the first time, the researchers defined the link between two cellular communications (signaling) systems that converge on the CRTC3 protein in melanocytes. These two systems instruct the cell to proliferate or produce the pigment melanin.

Montminy compares this process with a relay race. Typically, a baton, or chemical message, is transmitted from one protein to another until it arrives at the CRTC3 switch, which either turns it on or off.

“The fact that CRTC3 was an integration site for two signaling pathways—the relay race—was most surprising,” noted Montminy, who holds the J.W. Kieckhefer Foundation Chair. “CRTC3 makes a point of contact between them that increases the specificity of the signal.”

As a next step, the team intends to further analyze the mechanism of how CTRC3 affects the balance of melanocyte differentiation to achieve better insights into its role in cancer.

Source:

Journal reference:

Ostojić, J., et al. (2021) Transcriptional co-activator regulates melanocyte differentiation and oncogenesis by integrating cAMP and MAPK/ERK pathways. Cell Reports. doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109136.