Recent research published by Oxford University Press in Molecular Biology and Evolution demonstrates that Dupuytren’s disease is partially Neandertal in origin. Scientists were aware that the disease was more prevalent in Northern Europeans than in those of African ancestry.

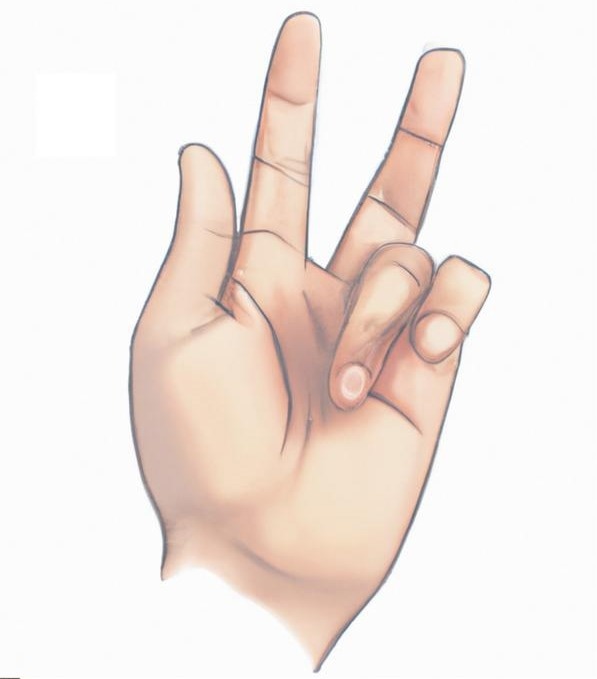

A ring finger locked in a bent position as seen in Dupuytren’s disease, colloquially known as the “Viking disease.” Image Credit: Hugo Zeberg/Molecular Biology and Evolution.

A ring finger locked in a bent position as seen in Dupuytren’s disease, colloquially known as the “Viking disease.” Image Credit: Hugo Zeberg/Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Dupuytren’s disease is a condition that affects the hand. Those who have the disease experience their hands becoming permanently bent in a flexed position. Although the disease can affect any finger, it most commonly affects the ring and middle fingers.

Numerous risk factors for the disease have already been found by scientists, including age, alcohol intake, diabetes, and genetic susceptibility. A 1999 Danish study found that the disease was heritable in 80% of cases, indicating a considerable genetic influence.

People of Northern European ancestry are substantially more likely to have the disorder. According to one study, the frequency of Dupuytren’s disease among Norwegians over the age of 60 could be as high as 30%.

However, the condition is uncommon in people of African descent. Because of its obvious geographic distribution, Dupuytren’s disease has earned the nickname “Viking disease.”

The proportion of genetic ancestry linking modern humans to now-extinct groups varies geographically. Individuals from Africa south of the Sahara have very little ancestry from Neandertals or Denisovans, who inhabited Europe and Asia until at least 42,000 years ago.

People with origins outside of Africa, on the other hand, inherited up to 2% of their genome from Neandertals, and some Asian populations today have up to 5% Denisovan ancestry. Because of these regional variations, archaic gene variants can lead to characteristics or diseases only seen in certain populations.

Given the prevalence of Dupuytren’s disease in Europeans, researchers looked into its genetic roots. They identified genetic risk variants for Dupuytren’s disease using data from 7,871 cases and 645,880 controls from the FinnGen R7 collection, UK Biobank, and the Michigan Genomics Initiative.

Researchers discovered 61 genome-wide significant variants linked to Dupuytren’s disease. Further investigation revealed that three of these variants, including the second and third most closely related ones, are of Neandertal origin.

The discovery that two of the most prominent genetic risk factors for Dupuytren’s disease are of Neandertal origin leads the researchers to believe that Neandertal ancestry has a substantial role in explaining the disease’s prevalence in Europe today.

This is a case where the meeting with Neanderthals has affected who suffers from illness, although we should not exaggerate the connection between Neanderthals and Vikings.

Hugo Zeberg, Study Lead Author, Karolinska Institutet,

Source:

Journal reference:

Ågren, R., et al. (2023). Major Genetic Risk Factors for Dupuytren’s Disease Are Inherited From Neandertals. Molecular Biology and Evolution. doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msad130.