“Programmed cell death protein 1,” or PD-1, has been considered a key target in cancer therapies since its discovery in the 1990s. The PD-1 protein functions as a type of off switch that prevents immune cells from attacking other cells. It is a “checkpoint” receptor that frequently appears on the surface of immune system cells.

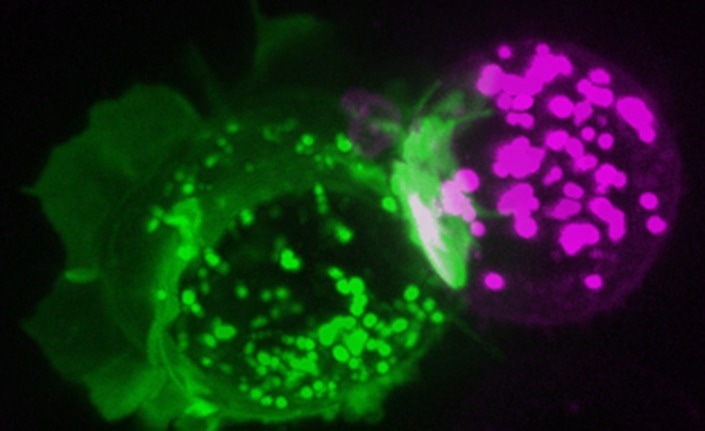

A 3-D image shows a T cell expressing the immune checkpoint receptor PD-1 (green) interacting with an antigen presenting cell expressing the ligand PD-L1 (magenta). Image Credit: University of California San Diego

A 3-D image shows a T cell expressing the immune checkpoint receptor PD-1 (green) interacting with an antigen presenting cell expressing the ligand PD-L1 (magenta). Image Credit: University of California San Diego

Scientists created novel drugs to suppress PD-1 and activate the body’s immune system to combat cancer after its discovery, which transformed oncology and won a 2018 Nobel Prize. However, only a tiny percentage of cancer patients respond well to treatments that use PD-1, underscoring the need for a better understanding of PD-1's mechanism of action.

Since rodent and human biology are thought to function similarly, a large portion of what is known about PD-1’s functions comes from research done on mice.

Now, researchers from the School of Biological Sciences and School of Medicine at UC San Diego have found that this assumption might not be accurate. The scientists from UC San Diego and their colleagues at the Chinese Academy of Sciences conducted a thorough evaluation of PD-1 that included new biochemical analyses, animal modeling, and a new evolutionary roadmap that traces PD-1 back millions of years. They discovered that PD-1 in mice is much weaker than in the human form.

Under the direction of assistant project scientist Takeya Masubuchi, the investigation identified several hitherto unidentified PD-1 characteristics, such as a “motif”—a particular amino acid sequence—that differs significantly between rodents and humans.

Our work uncovers unexpected species-specific features of PD-1 with implications for developing better pre-clinical models for PD-1. We found a motif in PD-1 that is present in most mammals, including humans, but is surprisingly missing in rodents, making rodent PD-1 uniquely weaker.”

Enfu Hui, Associate Professor and Study Senior Author, School of Biological Sciences, University of California San Diego

The journal Science Immunology published the study on January 3rd, 2025.

Although many proteins in mice and humans have similar sequences, receptors in the immune system often show greater differences. Our study shows that these sequence differences can lead to functional variations of immune checkpoint receptors across species.”

Takeya Masubuchi, School of Biological Sciences, University of California San Diego

To further their analysis, the researchers used co-senior author Professor Jack Bui's lab in the Department of Pathology to evaluate the effects of PD-1 humanization in mice, which involves substituting the human version of PD-1 with mouse PD-1. They discovered that the humanization of PD-1 interfered with T cells' ability to fight tumors.

This study shows that as science progresses we need to have a rigorous understanding of the model systems that we use to develop medicines and drugs. Finding that rodents might be outliers in terms of PD-1 activity forces us to rethink how to deploy medicines to people. If we have been testing medicines in rodents and they are really outliers, we might need better model systems.”

Jack D. Bui, Department of Pathology, University of California San Diego

Study co-senior author Professor Zhengting Zou and his colleagues from the Chinese Academy of Sciences worked with the researchers to track the evolution of PD-1 human-rodent distinctions. After the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) mass extinction event, which wiped off the (non-avian) dinosaurs, they found evidence of a significant decline in ancestral rodent PD-1 activity approximately 66 million years ago.

Among all vertebrates, the research revealed that the rodent PD-1 is the most weak. The weakness could be explained by unique ecological adaptations made to evade the impacts of infections that are peculiar to rodents.

“The rodent ancestors survived the extinction event but their immune receptor activities or landscape might have been altered as a consequence of adaptation to new environmental challenges,” added Hui.

Future research will evaluate how PD-1 affects T cell anti-tumor activity in a humanized setting for a range of tumor types.

Source:

Journal reference:

Masubuchi, T., et al. (2025) Functional differences between rodent and human PD-1 linked to evolutionary divergence. Science Immunology. doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.ads6295.